Tunuva Melim is a sister of the Priory. For fifty years, she has trained to slay wyrms.

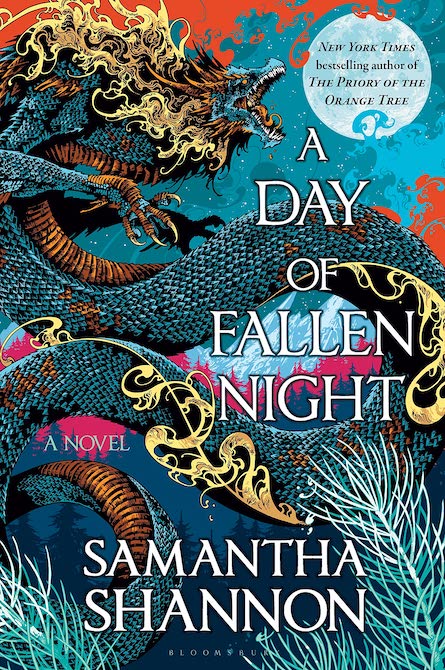

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from A Day of Fallen Night, the standalone prequel to The Priory of the Orange Tree by Samantha Shannon, out from Bloomsbury on February 28.

Tunuva Melim is a sister of the Priory. For fifty years, she has trained to slay wyrms—but none have appeared since the Nameless One, and the younger generation is starting to question the Priory’s purpose.

To the north, in the Queendom of Inys, Sabran the Ambitious has married the new King of Hróth, narrowly saving both realms from ruin. Their daughter, Glorian, trails in their shadow—exactly where she wants to be.

The dragons of the East have slept for centuries. Dumai has spent her life in a Seiikinese mountain temple, trying to wake the gods from their long slumber. Now someone from her mother’s past is coming to upend her fate.

When the Dreadmount erupts, bringing with it an age of terror and violence, these women must find the strength to protect humankind from a devastating threat.

3

South

‘Siyu, get down from there!’

The orange tree sighed in the breeze. Its gnarled trunk was always warm to the touch, as if there was sunlight trapped in its sapwood. Every leaf was polished and fragrant, and even deep in autumn, it bore fruit.

Not once, for however long it had stood here—since the dawn of time, perhaps—had anyone defiled its branches. Now a young woman crouched among them, barefoot and out of reach.

Buy the Book

A Day of Fallen Night

‘Tuva,’ she called down, her voice spiced with laughter, ‘it’s wonderful. I swear I could see all the way to Yikala!’

Tunuva stared up in dismay. Siyu had always been headstrong, but this could not be dismissed as youthful folly. This was sacrilege. The Prioress would be outraged when she heard.

‘What is it, Tunuva?’ Imsurin came to stand beside her, following her line of sight. ‘Mother save us,’ he said under his breath. He glanced back down at her. ‘Where is Esbar?’

She barely heard him, for Siyu was climbing again. With a last flash of sole, she ventured into the higher branches, and Tunuva started forward, a strangled sound escaping her.

‘You mustn’t—’ Imsurin began.

‘How do you suppose I would?’ Tunuva snapped. ‘I have no inkling of how she got up there.’ Imsurin raised his hands, and she turned back to the tree. ‘Siyu, please, enough of this!’

The only answer was a sparkling laugh. A green leaf fluttered to the ground.

By now, a small crowd had gathered in the valley: sisters, brothers, three of the ichneumons. Murmurs spiked behind Tunuva, like the hum from a nest of spindle wasps. She gazed up at the orange tree and prayed with all her might: Keep her safe, guide her to me, do not let her fall.

There was no way to conceal what had happened. A place kept secret for centuries could not afford secrets within its own walls.

‘We should find Esbar. Siyu listens to her,’ Imsurin said, with certainty. ‘And to you,’ he added, a clear afterthought. Tunuva pursed her lips. ‘You must get her down, before—’

‘She will not hear any of us now. We must wait for her to come to us.’ Tunuva pulled her shawl around her shoulders and folded her arms. ‘And it’s too late. Everyone has seen.’

By the time Siyu reappeared, the sky had flushed to apricot, and Tunuva was both rigid and atremble, like a plucked harpstring.

‘Siyu du Tunuva uq-Nāra, come down at once,’ she shouted. ‘The Prioress will hear of this!’

It was a craven thing, to invoke the Prioress. Esbar would never have been so weak. Still, her anger must have found its mark, for Siyu looked down from the branch, smile fading.

‘Coming,’ she said.

Tunuva had assumed she would come down the same way she had climbed up, whatever that had been. Instead, Siyu stood and found her balance. She was light and small, and the bough was strong, yet Tunuva watched in dread, thinking it would crack beneath her.

Not once had she feared the tree before this day. It had been guardian and giver and friend—never an enemy, never a threat. Not until Siyu ran along the bough and leapt into open air.

In unison, Tunuva and Imsurin rushed forward, as if they had any hope of catching her. Siyu plummeted with a shriek, arms wheeling, and disappeared into the crashing waters of the Minara. Tunuva cast herself down at the riverbank.

‘Siyu!’

Her chest was so tight she could scarcely breathe. She flung off her shawl, and would have dived in—had Siyu not surfaced, black hair slicked across her face, and let out a laugh of pure delight. Fanning her strong arms, she kicked against the flow of water.

‘Siyu,’ Imsurin said, his voice hard and strained, ‘do not tempt Abaso’s rage.’ He reached for her. ‘Climb out, please.’

‘You always said I swam beautifully, Imin,’ came the overjoyed reply. ‘The water is bracing. Try it!’

Tunuva looked to Imsurin. Decades of knowing him, and never once had she seen fear on that raw-boned face. Now his jaw shook. When Tunuva lowered her gaze, she found her hands were quaking.

It’s all right. She’s all right.

Siyu grasped one of the roots and used it to drag herself from the river. Tunuva released her breath, the tension pulled from her at once. She wrenched Siyu into her arms and kissed her sodden hair.

‘Reckless, foolish child.’ Tunuva clasped the back of her head. ‘What were you thinking, Siyu?’

‘Do you mean to tell me no one has ever done it?’ Siyu said, breathless with exhilaration. ‘Hundreds of years with such a tree, and no one ever climbed it? I am the very first?’

‘Let us hope you are the last.’

Tunuva retrieved her shawl and draped it around Siyu. Autumns were mild in the Lasian Basin, but the River Minara stemmed from the northeastern mountains, far beyond the natural heat that warmed the land around the tree.

When they stood, Siyu nudged her, smiling. Tunuva alone saw their sisters’ flinty gazes. She curled an arm around Siyu and walked her across the cool grass of the vale, to the thousand steps that would take them to the Priory.

***

More than five hundred years had passed since its founding—since Cleolind Onjenyu, Princess of Lasia, had defeated the Nameless One.

The orange tree had decided that battle. When Cleolind had eaten its fruit, she had become a living ember, a vessel of the sacred flame, giving her the strength to defeat the beast. The tree had saved her from his fire and graced her with its own.

One day, he would return. Cleolind had been sure of that.

The Priory was her legacy. A house of women, raised as warriors, sworn to defend the world from the offspring of the Dreadmount. To listen for any whisper of his wings.

The first sisters had discovered a honeycomb of caves in the steep red cliffs that walled the Vale of Blood. In the decades that followed, they had dug further and deeper, and their descendants had continued their work, until there was a hidden stronghold in the rock.

It was only in the last century that beauty had been kindled there. Shale and pearl mantle inlaid the columns, and the ceilings were mirrored or painted in styles from across the whole of the South. The first hollows scraped out for lamps had been shaped into elegant arches, each lined with gold leaf to heighten the candlelight. Fresh air whispered into the caves from above, flowing through carven latticework doors, laced with the scents of the flowers the men grew. A strong wind might add the fragrance of oranges.

There was still a great deal of work to be done. When Esbar was Prioress, she meant to oversee the construction of a skygazing pool, with stove-heated water and pipes, and to use a clever arrangement of mirrors to bend daylight into the deepest caves. Esbar meant to do many things when the red cloak fell upon her shoulders.

Every day, Tunuva thanked the Mother for their home. This place had sheltered them from the avaricious eyes of the world. Here, there were no monarchs to force them to their knees, no coin to make them rich or poor, no tolls on their waters or tax on their crops. Cleolind had renounced her own crown to build a place where there was no need of them.

Siyu spoke first. ‘Will the Prioress punish me?’

‘I imagine so.’

Tunuva kept her tone flat. Siyu bristled. ‘There was no harm in it,’ she said, thorns in her voice. ‘I’ve always wanted to climb the tree. I don’t see why everyone must be so—’

‘It is not my place to teach you right from wrong, Siyu uq-Nāra. You ought to know it well by now.’ Tunuva looked sidelong at her. ‘How did you reach the branches?’

‘I threw up a length of rope. It took a month to knot one long enough.’ Siyu gave her a coy smile. ‘Why, Tuva—would you like to try it?’

‘You have been enough of a fool today, Siyu. I am in no mood for jests,’ Tunuva said. ‘Where is this rope now?’

‘I left it on the branch.’

‘Then someone will have to recover it, and the tree will be defiled a second time.’

After a pause, Siyu said, ‘Yes, sister.’

She had the sense to hold her tongue for the rest of the long walk.

At the age of ten, Siyu had been moved from where the infants and young children slept. Now she was seventeen and lived on the level below the initiates. Though she was old enough to join them, the Prioress had not yet deemed her worthy of the flame.

Tunuva opened the door to the right chamber. The lamps had all been lit, herbs left on the pillow. The men took special care to freshen the inner chambers, where sunlight never reached.

She conjured a small flame and let it drift away from her palm. Siyu drew the shawl closer as she watched it flicker above them, her long dark eyes reflecting its light. It sank towards the stove and caught the tinder. Bright flames leapt and burned without smoke.

Siyu peeled off her drape and knelt on the rug by the fire, rubbing her arms. Only when she ate of the fruit would she know how it felt to be warm all the way through. Tunuva had hoped that day would come soon. Now it seemed farther away than ever.

‘Where is Lalhar?’ she asked Siyu shortly.

‘I thought she might bark if she saw me climb. Yeleni said she could sleep in her room.’

‘Your ichneumon is your responsibility.’ Tunuva stripped a layer from the bed. ‘Yeleni knew your plans, then.’

Siyu snorted. ‘No.’ She raked her fingers through the ends of her hair. ‘I knew she would stop me.’

‘One of you has sense, at least.’

‘Are you very angry, Tuva?’ When Tunuva only wrapped the heavy woven mantle around her, Siyu watched her face. ‘I frightened you. Did you think I would fall?’

‘Did you think you would not?’ Tunuva straightened. ‘Arrogance does not become a future slayer.’

Siyu stared at the stove. A ripple of dark hair clung to her cheek.

‘You could speak to the Prioress,’ she said. ‘She might not be so hard on me if you—’

‘I will not defend what you have done, Siyu. You are not a child any longer.’ Tunuva picked up her damp shawl. ‘Allow me to offer you a piece of advice, as one whose name you carry. Reflect on what you have done, and when the Prioress summons you, accept your punishment with grace.’

Siyu clenched her jaw. Tunuva turned to leave.

‘Tuva,’ Siyu said suddenly, ‘I’m sorry I scared you. I will apologise to Imin, too.’

Tunuva glanced back at her, softening. ‘I will… ask him to bring you some buttermilk,’ she said, feeling a stab of frustration at herself. She left the room and walked back down the corridor.

Half a century she had served the Mother. By now, she should be folded steel, each year making her stronger, harder—yet when it came to Siyu, she bent like sweetgrass in the wind. She took the stairs to the open side of the Priory, where torches fluttered in a breeze.

Before she knew it, she was in the highest corridor, tapping on the highest door. A hoarse voice bade her enter, and then she was standing before the woman who presided over the Priory.

Saghul Yedanya had been elected Prioress when she was only thirty. Her head of black curls had long since turned white, and where she had once been among the tallest and sturdiest women in the Priory, her chair of polished wood now seemed too large for her.

Still she sat upon it proudly, hands clasped on her stomach. Her face, mostly brown, was dappled with pallor, which also flecked her fingertips and formed a tilted crescent on her throat. Deep lines were carved across her brow. Tunuva envied such discernible wisdom—when every year could be read on the skin, laid out like the rings of growth in a tree.

Esbar sat opposite, pouring from a gold-rimmed jar. Seeing Tunuva, she arched an eyebrow.

‘Who comes at this hour?’ Saghul asked in her deep, slow voice. ‘Is that you, Tunuva Melim?’

‘Yes,’ Tunuva said. Clearly they had not heard what had happened. ‘Prioress, I came from the vale. One of our younger sisters has… climbed upon the tree.’

Saghul tilted her head. ‘Who?’ Esbar asked, perilously soft. ‘Tuva, who has done this?’

Tunuva braced herself. ‘Siyu.’

At once, Esbar was on her feet, expression thunderous. Tunuva moved to block her, or try, but Saghul spoke first: ‘Esbar, remember your place.’ Esbar stopped. ‘If you wish to serve me as munguna, calm and comfort your sisters. This sight must have disturbed them.’

Esbar collected her breath, pouring sand on the fires within. ‘Yes, Prioress,’ she said curtly. ‘Of course.’

She touched Tunuva on the arm and was gone. Tunuva knew she would still make her wrath known to Siyu.

‘Wine,’ Saghul said. Tunuva took the empty seat and finished serving it. ‘Tell me what happened.’

Tunuva did. Better that it came from her. Saghul never touched the wine as she listened, gazing towards the opposite wall. Her pupils were grey instead of black, a condition that clouded her sight.

‘Did she disturb the fruit?’ she finally asked. ‘Did she eat when it was not given?’

‘No.’

There was silence for a time. Somewhere above, a bay owl called out.

‘Siyu is spirited and adventurous. A hard thing in a world as small as ours,’ Tunuva said. Saghul conceded with a grunt. ‘I know she must be reprimanded for this desecration, but she is still young.’

‘Does she regret it?’

It was a moment before Tunuva said, ‘I believe she will. Once she has reflected.’

‘If she does not regret it now, she never will. We impress a deep respect for the tree on our children, Tunuva. They learn it before they learn to write or read or fight,’ Saghul pointed out. ‘There are two-year-olds among us who know they cannot climb upon its branches.’

Tunuva was at a loss for a counterstroke. Saghul walked her fingertips towards the cup of wine, finding its base.

‘I fear this is only the beginning,’ she muttered. ‘There is a rot at the heart of the Priory.’

‘Rot?’

‘More than five centuries since the Mother vanquished the Nameless One in this valley,’ Saghul reminded her, ‘and there has been no sign that he will ever return. It was inevitable that some among us would begin to question the need for the Priory.’

Tunuva drank a small measure of wine. It did nothing to solve the drought in her mouth.

‘What Siyu did, profane though it is, is only a sign of the decay. She does not respect the tree any longer, because she does not fear the beast from which it shielded Cleolind Onjenyu,’ Saghul said grimly. ‘The Nameless One is a fable to her. To all of us. Even you, Tunuva, who are so loyal to our house, must have asked yourself why we remain.’

Tunuva lowered her gaze.

‘When I first left,’ she confessed, ‘I walked in the Crimson Desert, the sun beating down on my skin, and I understood how wide and glorious the world must be; how many marvels it must hold. I did question, then, why we choose to hide in a small corner of it.’

She remembered it so clearly. Her very first journey beyond the Vale of Blood, Esbar riding at her side. Saghul had sent them to harvest a rare moss that grew on Mount Enunsa—a task that would take them away from their home, but not to any settlements.

Growing up, Tunuva had always found Esbar intimidating, with her sharp tongue and her indestructible confidence. Esbar had thought Tunuva prim and joyless. Still, they had always known they would take their first steps beyond the Priory together, given their closeness in age.

The year before the journey, all had changed when Tunuva was chosen to duel Gashan Janudin. Since they were children, Esbar and Gashan had been rivals, each determined to one day be Prioress. So intense was their competition, their certainty that no one else could match them, that Gashan had not concealed her disdain when Tunuva approached.

Before then, Tunuva had always underplayed her skill with a spear, seeing no need to show off to her sisters—but suddenly, she had felt weary of Gashan and Esbar, two suns overlooking the bright stars around them. She had slammed all her years of dutiful study into her weapon, and before Gashan had quite seen the danger, Tunuva had disarmed her.

That night, Esbar had found her on a balcony, stretching to keep her body limber. You, Esbar had said, sitting down uninvited, have finally caught my attention. She had come bearing wine, and poured two cups. When did the quiet conformist nurture such a talent with a spear?

You call it conforming; I call it surrender to the Mother. Tunuva had joined her on the steps. And you might find me less quiet if you had ever paused to speak to me.

Esbar had taken her point. They had spent that night getting to know one another, finding an unexpected warmth. By the time they went their separate ways, the sun had risen.

After that, they were far more aware of each other. Esbar would catch her eye in corridors, find reasons to pass her room, stop to talk when their paths crossed. And then they were both twenty, and the day had come for their first steps outside.

For a moment, Tunuva was lost in the past. The cruel beauty of the desert. How small her existence had seemed in the face of it. How the sand had sparkled like shattered ruby. They had left their ichneumons by a panhole and continued the approach on foot. She had never seen so much dazzling blue sky, unbounded by trees or the slopes of their valley. They were without their sisters, alone in a sea of sand, and yet anyone could find them.

She and Esbar had looked at each other in wonder. Later, they realised they had both felt it: a sense not just that the world had changed, but that they, too, were new. It must have been that feeling that had made Esbar kiss her. Breathless with laughter, they had embraced on the soft warmth of the dune, the sky almost too blue to bear, sand running like silk beneath their bodies, breath catching fire.

Thirty years had passed, and still Tunuva trembled at that memory. She was suddenly conscious of her drape against her breasts, and a richening ache in the base of her belly.

‘Why did you return?’ Saghul asked, drawing her back. ‘Why not stay in the wide and glorious world for ever, Tunuva?’

Esbar had asked the same question that day, when they lay in the shade of a rock. They had both looked as if they were freckled with blood, covered in those glistening red grains.

‘Because it made me understand my duty,’ Tunuva said. ‘It was laying eyes upon the world, being part of it, that made me appreciate the importance of protecting it. If the Nameless One does return, we may be the only ones who can—so I will remember. I will remain.’

Saghul smiled. A warm, true smile that creased the corners of her eyes and served to deepen her beauty.

‘I know you still think Siyu too callow to eat of the fruit,’ Tunuva said. ‘I know the grave risk in making her an initiate before the time is right. I also know this… error of judgement, this foolish violation, cannot have convinced you of her maturity, Saghul.’

‘Hm.’

‘But Siyu may need to fall in love with the outside, as I did. Let her ride to the golden court of Lasia and guard Princess Jenyedi. Let her taste of the wonders of the world, so she may understand the importance of the Priory. Let her never think of this place as her cage.’

Silence stretched wide between them. Saghul took a long drink from her cup.

‘Sun wine,’ she said, ‘is among the wonders of the ancient world.’

Tunuva waited. When the Prioress of the Orange Tree told a story, it always had meaning.

‘It costs a great deal to bring it here from Kumenga,’ Saghul went on. ‘I ought not to risk it, but if I have no supply on hand, I find it seeps into my dreams, and I wake with the taste of it on my tongue. To me, nothing but the sacred fruit is sweeter. And yet… I leave half in the cup.’

She placed it between them. The sound of ceramic on wood rang loud in the still room.

‘Some have the restraint to taste of worldly pleasure,’ she said. ‘You and I are among them, Tunuva. When I found you with Esbar the first time, I feared you would lose yourselves to your passion. You proved me wrong. You knew how much of the wine to taste. You knew to leave some in the cup.’ This time, when she smiled, there was no warmth in it. ‘But some, Tunuva—some would drink of the sweet wine until they drowned.’

With one knotted finger, she tipped the cup. Sun wine spilled across the table and dripped like watered honey to the floor.

Excerpted from A Day of Fallen Night, copyright © 2022 by Samantha Shannon.